The success of New York’s High Line sparked a whole series of similar public spaces around the world. It is one of the most striking and influential public-realm projects of the early 21st century, resonating globally. Built on a disused railway spur, the High Line has become both a New York landmark and a prototype for creating linear parks in many countries.

Linear parks are elongated green public spaces that simultaneously serve as places for rest, pedestrian corridors, and urban attractors. In today’s metropolis, their hallmark is multifunctionality: a rich palette of activities, services, and events that allow people to enjoy varied, engaging leisure. The development of such parks increases the appeal of neighborhoods and of the city as a whole.

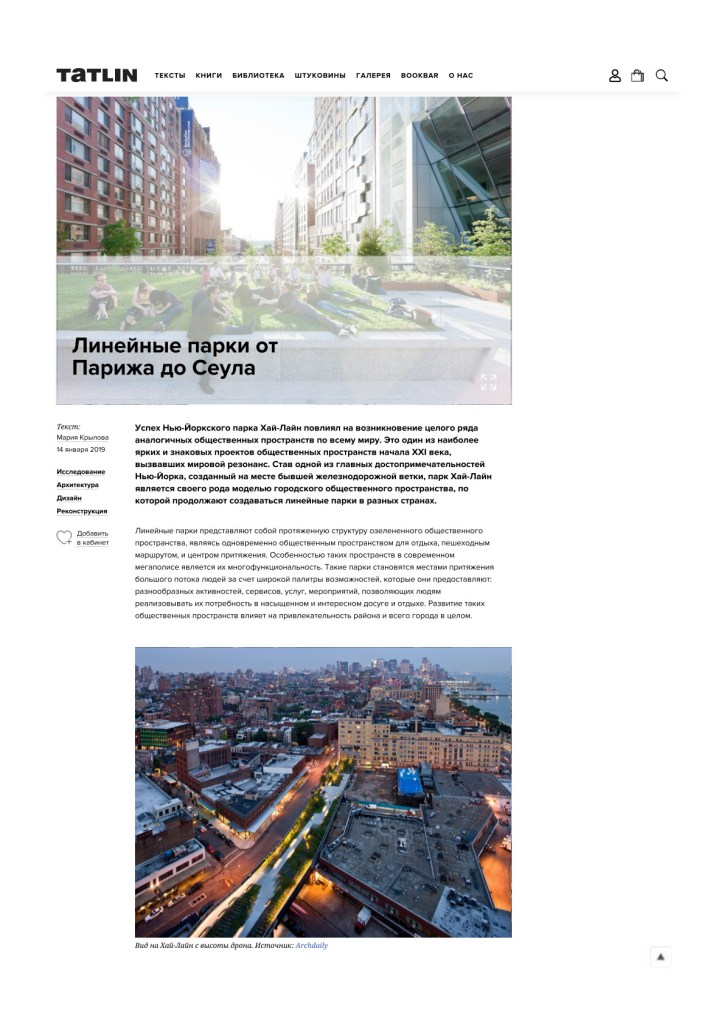

Fig. 1. Aerial view of the High Line. Source: ArchDaily.

Origins of the Typology

A proponent of linear parks as early as the late 19th century was Frederick Law Olmsted, one of the first landscape architects in the United States and co-author of Central Park in New York. In 1893 he designed a linear park for the city of Hart, Virginia, but it was never built.

Later, the idea of linear greenways gained momentum in the 1960s–70s in the U.S., driven by a growing need for public spaces and by the rising number of disused transport corridors. The conversion of abandoned rail lines became known as “Rail-to-Trail.”

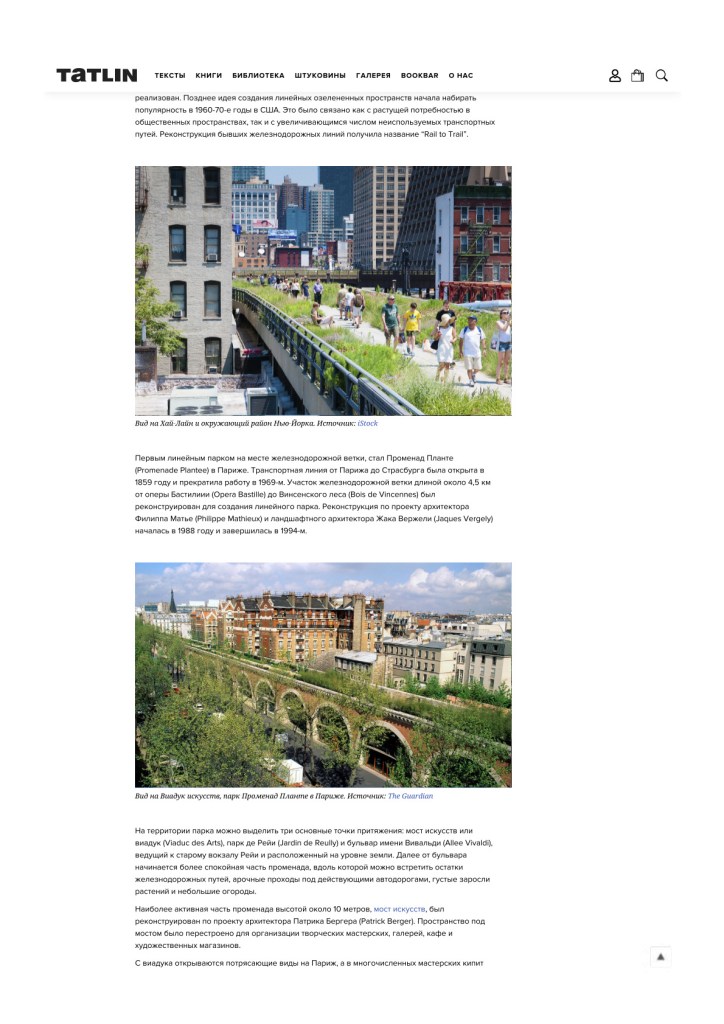

Fig. 2. The High Line within its Manhattan context. Source: iStock.

Paris Precedent: Promenade Plantée

One of the first linear parks on a former rail line was Promenade Plantée in Paris. The Paris–Strasbourg line opened in 1859 and ceased operations in 1969. A section of about 4.5 km, from the Opéra Bastille to the Bois de Vincennes, was transformed into a linear park. The reconstruction, designed by Philippe Mathieux and landscape architect Jacques Vergely, began in 1988 and finished in 1994.

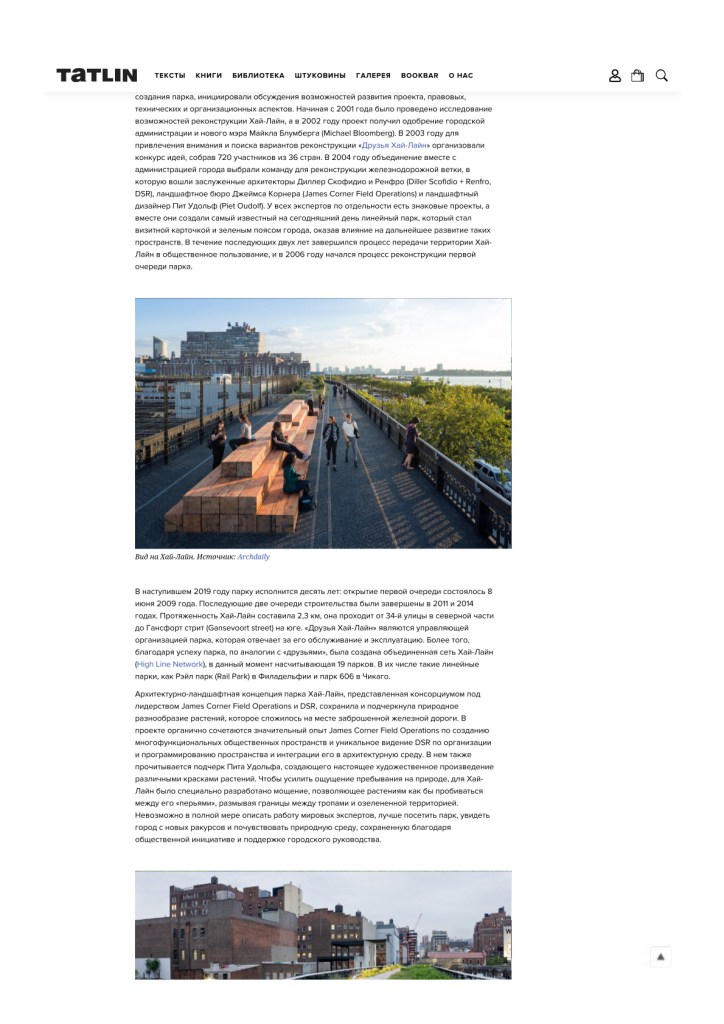

Fig. 3. View of the Viaduc des Arts on the Promenade Plantée, Paris. Source: The Guardian.

Within the park three main attractors stand out: the Viaduc des Arts (the “bridge of arts”), Jardin de Reuilly, and Allée Vivaldi leading to the former Reuilly station at ground level. Beyond this boulevard begins a calmer stretch of the promenade where one encounters remnants of the railway, arched passages under live roads, dense plantings, and small allotment gardens.

The most active segment — the Viaduc des Arts, about 10 meters above ground — was redesigned by architect Patrick Berger. The space beneath the arches was converted into workshops, galleries, cafés, and art shops. From the viaduct there are superb vistas of Paris, while the numerous ateliers below hum with creativity. From the promenade you can descend into Jardin de Reuilly with its expansive lawn; the following segment runs at grade.

The Promenade Plantée links the central city to more distant quarters via a green pedestrian route. It lets you see Paris from unusual angles while still feeling immersed in a natural setting. What now seems an obvious solution — turning a derelict rail line into a green artery — was, at the time, a pioneering project that fit organically into the existing urban fabric and opened new perspectives on the city.

Fig. 4. View of Paris from the Promenade Plantée. Source: Condé Nast Traveler.

New York’s High Line

Like its Paris predecessor, New York’s High Line sits on a former elevated railway that was initially slated for complete demolition. Built in 1934 roughly 10 meters above street level to deliver freight to factories in Lower Manhattan, the line operated until the 1960s, when its southern portion was dismantled. Two decades later the remaining structure deteriorated further, and by the late 1990s the mayor had signed an agreement to demolish the High Line.

For the owner, CSX Transport Corporation, demolition meant significant cost. CSX commissioned the Regional Plan Association (RPA) to study either restoring the transport function or finding alternative uses. RPA found no viable transport reuse but recommended reconstruction as a green pedestrian route. The report was presented at public hearings, catching the attention of two local residents — Joshua David and Robert Hammond — who in 1999 founded the non-profit Friends of the High Line to advocate for preserving the structure and turning it into a public space.

Fig. 5. High Line, New York. Source: ArchDaily.

“Friends of the High Line” organization began gathering supporters and experts, initiating discussions on legal, technical, and organizational aspects. From 2001, feasibility studies were conducted; in 2002 the project gained approval from City Hall and the new mayor, Michael Bloomberg. In 2003, to raise awareness and explore options, Friends of the High Line launched an ideas competition, attracting 720 entries from 36 countries. In 2004, the City and the non-profit selected the design team: architects Diller Scofidio + Renfro (DSR), landscape architects James Corner Field Operations, and landscape architect Piet Oudolf. Each brought landmark experience — and together they created the world’s most famous linear park, a green spine and calling card for the city, influencing the evolution of similar spaces worldwide. Over the next two years, the High Line was transferred to public use, and in 2006 reconstruction of the first section began.

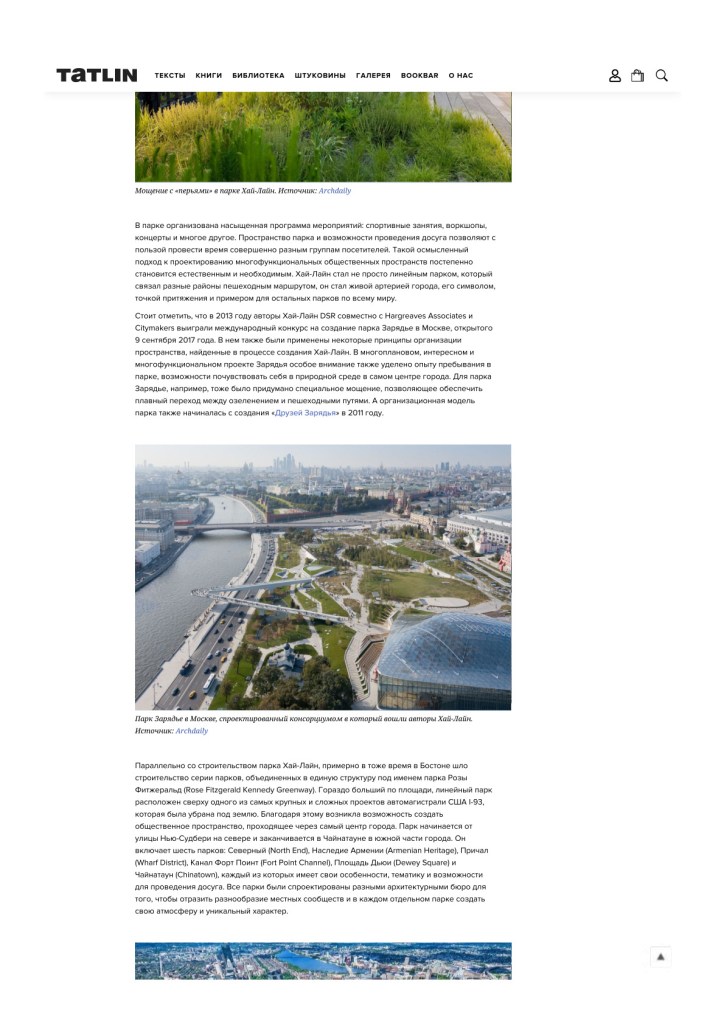

Fig. 6. View along the High Line. Source: ArchDaily.

The park turned ten in 2019: the first section opened on 8 June 2009; the next two followed in 2011 and 2014. The High Line runs for 2.3 km — from 34th Street in the north to Gansevoort Street in the south. Friends of the High Line operate and maintain the park. Building on its success, the “High Line Network” organization was created — now comprising 19 parks, including Rail Park in Philadelphia and The 606 in Chicago.

The design concept by James Corner Field Operations + DSR preserved and celebrated the spontaneous plant communities that had colonized the abandoned tracks, while Piet Oudolf’s planting turned the landscape into living art. To heighten the sense of nature, bespoke plank paving was developed so vegetation could “push through the seams,” softening the edge between paths and planting.

Fig. 7. High Line’s bespoke “plank” paving detail. Source: ArchDaily.

Programming is robust: sports classes, workshops, concerts, and more. This thoughtful approach to multifunctional public space is increasingly seen as essential. The High Line is not just a linear park linking neighborhoods; it has become a living artery, a symbol of the city, an attractor, and a model for parks worldwide.

From New York to Moscow: Zaryadye Park.

In 2013, the authors of the High Line, DSR, together with Hargreaves Associates and Citymakers, won the international competition to design Zaryadye Park in Moscow (opened 9 September 2017). The project adopted several principles tested on the High Line: a layered, multifunctional public realm and an emphasis on the visitor’s experience of nature in the city center. Zaryadye also features custom paving to create seamless transitions between planting and pedestrian routes. Organizationally, the park began with the formation of “Friends of Zaryadye” in 2011.

Fig. 8. Zaryadye Park, Moscow — the winning consortium included the authors of the High Line. Source: ArchDaily.

Boston’s Greenway

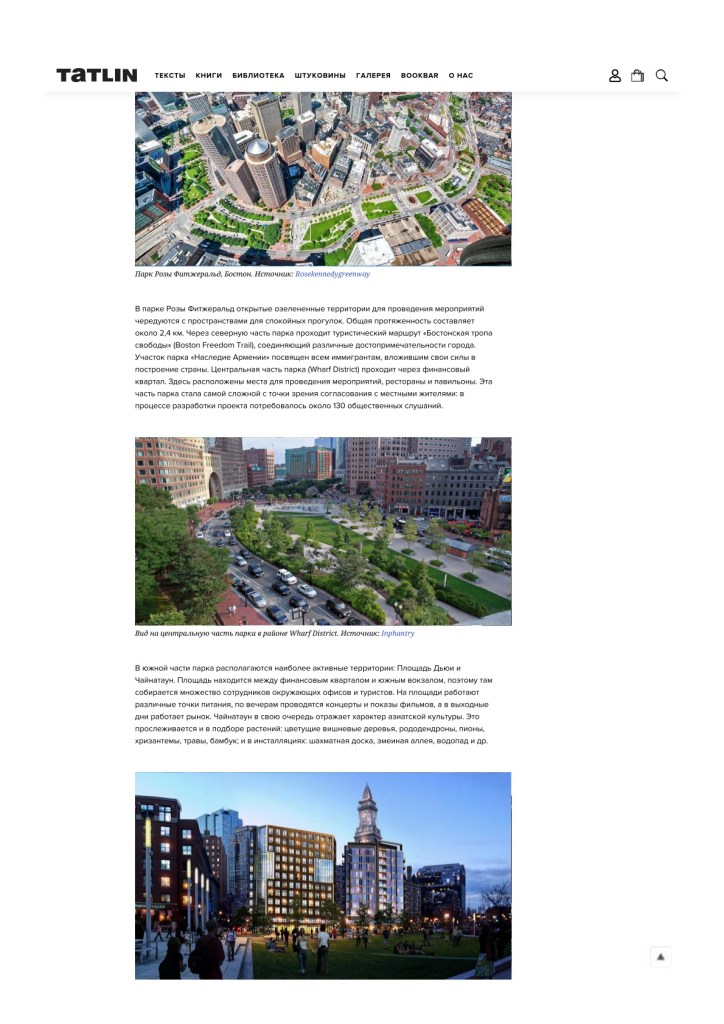

In parallel with the High Line, Boston built a chain of parks unified as the Rose Fitzgerald Kennedy Greenway. Much larger in area, this linear park sits above one of the most complex U.S. infrastructure projects, the I-93 motorway, which was buried underground. The opportunity created a public space through the heart of the city, from New Sudbury Street in the north to Chinatown in the south.

The Greenway comprises six parks — North End, Armenian Heritage, Wharf District, Fort Point Channel, Dewey Square, and Chinatown — each with its own theme, atmosphere, and leisure options, and each designed by different architecture and landscape offices to reflect the diversity of local communities.

Fig. 9. Rose Fitzgerald Kennedy Greenway, Boston. Source: rosekennedygreenway.org.

Open green event lawns alternate with quiet promenades. The total length is about 2.4 km. The northern sector intersects the Boston Freedom Trail, linking many of the city’s key sights. The Armenian Heritage Park honors immigrants who built the country. The central Wharf District runs through the Financial District, with event spaces, restaurants, and pavilions. This portion proved the most challenging in terms of public approval: around 130 hearings were held during design.

Fig. 10. Central Greenway near the Wharf District. Source: Inphantry.

In the south, the most active areas are Dewey Square and Chinatown. Dewey Square, between the Financial District and South Station, attracts office workers and tourists; food vendors operate there, concerts and film screenings take place in the evenings, and a market runs on weekends. Chinatown reflects the spirit of Asian culture — both in planting (cherry trees, rhododendrons, peonies, chrysanthemums, ornamental grasses, bamboo) and in installations (a chessboard, a “snake alley”, a waterfall, etc.).

Fig. 11. Market Street area, central Greenway. Source: Bizjournals.

In the early years the park faced criticism. After the prolonged construction works, residents expected an immediate step-change in quality. The non-profit Greenway Conservancy only took over operations the year after opening (2009), so at first the park felt sparse. Both plants and people needed time to settle in and fill the space with life.

Fig. 12. Installation by Janet Echelman. Source: Fuller Craft Museum.

Despite sharing a common typology inspired by the High Line, each subsequent park develops its own distinct identity through integration with the existing urban context. During implementation, the needs and perspectives of residents are carefully considered. In this way, every park both reflects and reinforces the character of its surroundings.

Beyond the creation of a physical green corridor linking different parts of the city, each linear park also establishes its own individual program of events and activities. When speaking of activities, events, and services, it is worth distinguishing between them. Activities are what a visitor can personally do in the park — cycling, relaxing, having picnics, playing badminton, and so on. If a visitor needs to rent a bicycle or sports equipment, this is part of the park’s service offer. Events, on the other hand, are organized occasions that require special coordination by the park administration — concerts, workshops, markets, or festivals. In most cases, the management team strives to provide the widest possible range of leisure options so that visitors spend more time in the park, thereby enhancing its economic appeal and social vitality.

Park Chicago’s 606.

Fig. 13. West side of The 606, Chicago. Source: Bloomingdale Trail.

Opened in 2015, The Park 606 occupies the former Bloomingdale Trail, a 4.3-km elevated freight line. It is part of the High Line Network. The project united several neighborhood groups and was delivered as a public-private partnership.

Built in 1913, the Bloomingdale line operated until the 1990s. Early steps toward the park included plans to integrate the corridor into a citywide cycle route, subsequent public hearings, and the creation of Friends of the Bloomingdale Trail in 2003. In 2004, the possibility of the park was written into the Logan Square Open Space Plan, approved by Mayor Richard M. Daley — under whom the Millennium Park also opened that year. Lead designers were MVVA (Michael Van Valkenburgh Associates) with Ross Barney Architects; construction began in 2013, and the first section opened two years later.

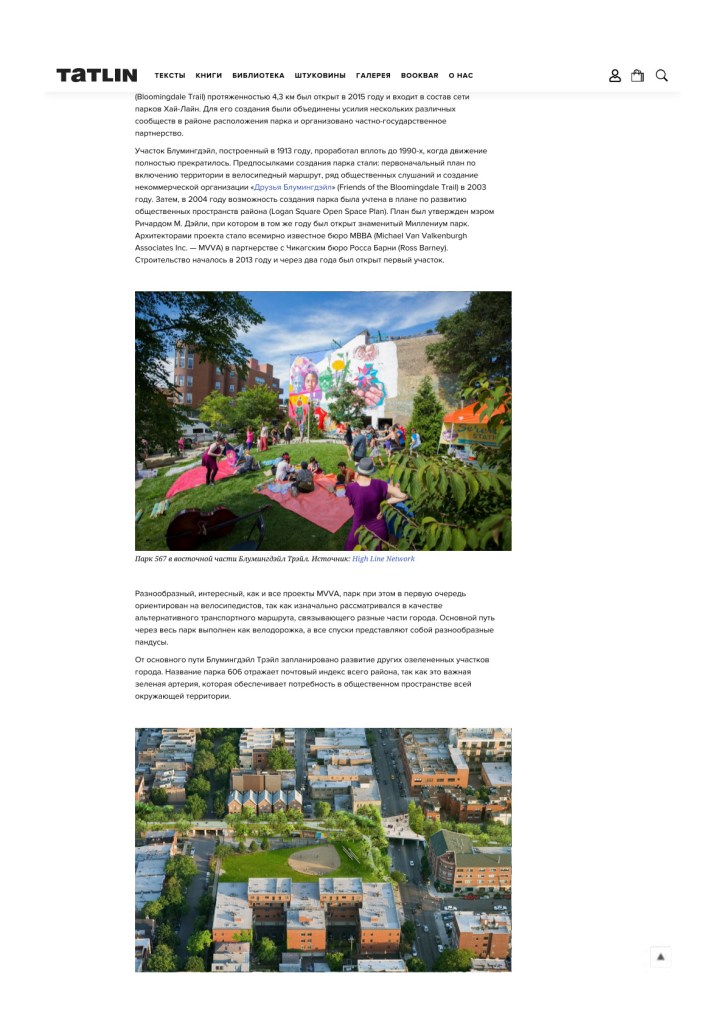

Fig. 14. Park 567 at the east end of the Bloomingdale Trail. Source: High Line Network.

As with many MVVA projects, The Park 606 is rich and varied, yet primarily oriented toward cyclists — conceived as an alternative transport route connecting parts of the city. The main path is a cycle track; all descents are ramps. From the Bloomingdale spine, further green spurs are planned into adjoining areas. The name “606” echoes the ZIP code prefix covering much of the city — a nod to the park’s role as a green artery for surrounding neighbourhoods.

Fig. 15. Churchill Park at the east end of the Bloomingdale Trail. Source: ArchDaily.

Sydney’s Goods Line

In 2015, Sydney opened a High-Line-like linear park with a similar name: the Goods Line. Built on a railway that operated from 1855 to 1984, it is multifunctional, with event spaces and strong links to Media Institution designed by Frank Gehry.

The park designed by ASPECT Studios with CHROFI for the state authority NSW, the park is only about 500 metress long, running from the Powerhouse Museum in the north to Central Station.

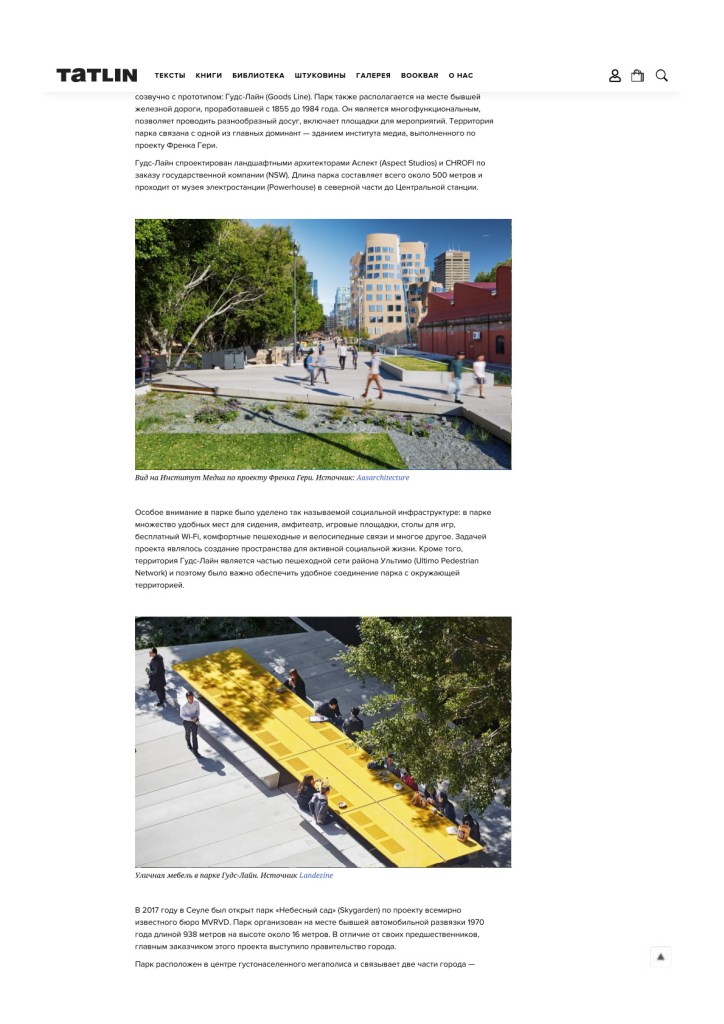

Fig. 16. UTS Business School by Frank Gehry, adjacent to the Goods Line. Source: Aasarchitecture.

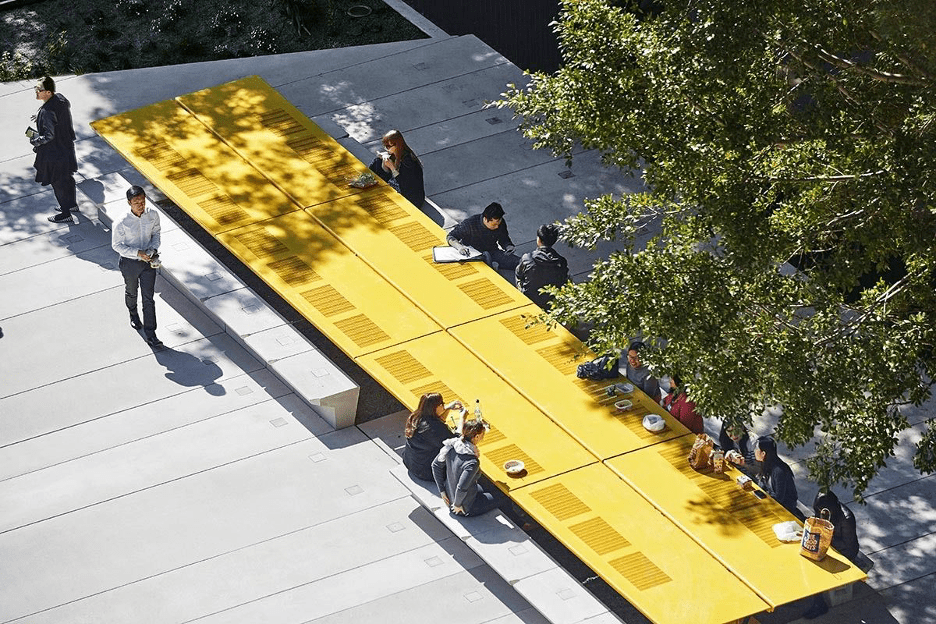

Particular emphasis was placed on social infrastructure: plentiful seating, an amphitheater, play areas, games tables, free Wi-Fi, comfortable walking and cycling links, and more — designed to enable active social life. The Goods Line also forms part of the Ultimo Pedestrian Network, so seamless connections to the surrounding area were essential.

Fig. 17. Urban furniture on the Goods Line. Source: Landezine.

Seoul’s Skygarden

In 2017, Seoul opened Skygarden designed by MVRDV — a 983-metre-long park on a 1970 motorway overpass, about 16 meters above ground. Here the city government itself acted as client. The park links the west and east sides of central Seoul over rail lines and a wide highway, transforming a noisy, crowded place into a pleasant pedestrian environment. It features around 24,000 plants — trees, shrubs, and flowers — arranged into small, themed gardens. In places, large circular planters create the impression of a fully-fledged green park, visually screening the traffic below.

Fig. 18. “Skygarden” by MVRDV, Seoul. Source: ArchDaily.

In addition to its primary function as a pedestrian crossing over one of the city’s major transport arteries, the linear park also serves as an urban attractor — a viewing platform, a comfortable public environment, and an active city center. The park’s pedestrian route is connected to the surrounding urban fabric through numerous stairways, ramps, and retail spaces. Future development plans for the area include further landscaping and greening of the adjacent neighborhoods.

It is worth noting that Seoul already had prior experience of transforming abandoned urban infrastructure into a linear park. The first and most well-known example of this type was the restoration of the Cheonggyecheon stream, a waterway running for more than 10 kilometers through the city center. Once buried beneath an elevated highway, the stream was later uncovered and completely revitalized, becoming a green oasis in the heart of the metropolis. As with the Skygarden, the initiative for Cheonggyecheon’s restoration came from the public sector, but the project’s implementation was carried out in partnership with private investors.

Fig. 19. Cheonggyecheon linear park, Seoul. Source: Smart Magazine.

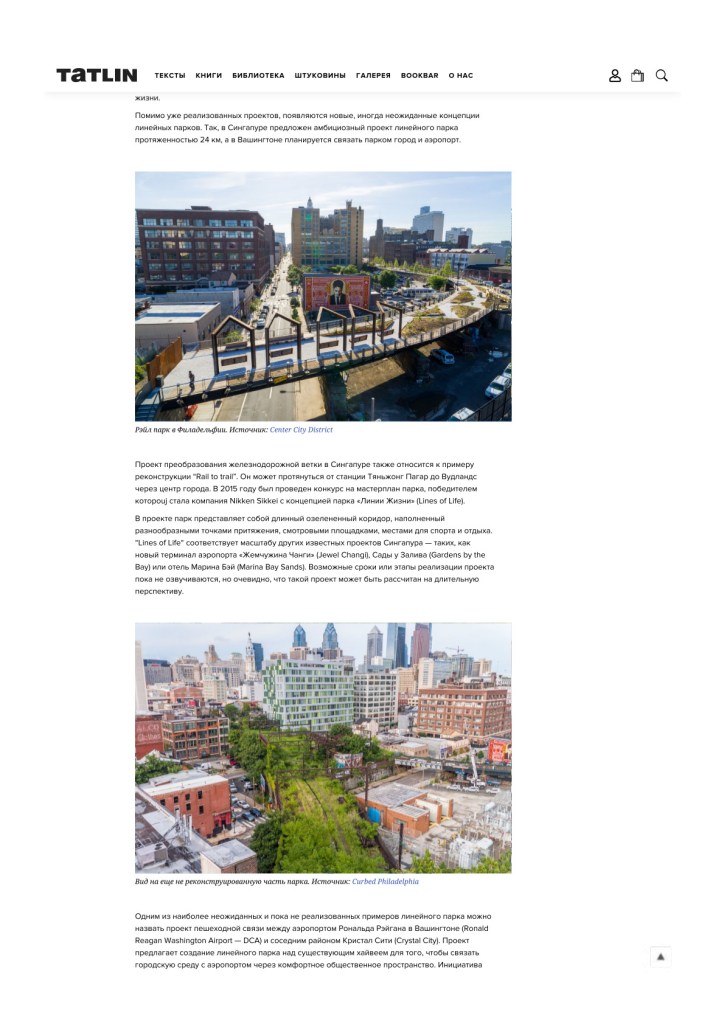

Philadelphia’s Rail Park

On 14 June 2018, the first phase of Rail Park opened in Philadelphia. Being part of the High Line Network, it is also located on the site of an abandoned railway line. To realize the project, a public partnership was formed in 2010 between the civic initiative Friends of the Rail Park (Center City District) and various municipal departments. Plans for the park’s long-term development include three additional construction phases.

Fig. 20. Rail Park, Philadelphia. Source: Center City District.

The newly opened section, less than one kilometer long, was designed by landscape architect Bryan Hanes (Studio Bryan Hanes) in collaboration with engineers from Urban Engineers. Further expansion of the park will create pedestrian connections between multiple city districts, offering diverse recreational opportunities and serving as a platform for active social life.

Fig. 21. Unrestored segment of the future park. Source: Curbed Philadelphia.

Ambitious new concepts: Singapore and Washington, D.C.

In addition to the projects that have already been completed, new and sometimes unexpected concepts for linear parks continue to emerge. Singapore has proposed an ambitious 24-km linear park, another Rail-to-Trail conversion stretching from Tanjong Pagar Station to Woodlands through the city center. In 2015, a master-plan competition selected Nikken Sekkei with the concept “Lines of Life.” The vision is a long green corridor filled with attractors, viewpoints, and places for sport and rest, comparable in scale to the city’s other signature projects — Jewel Changi, Gardens by the Bay, and Marina Bay Sands. Timelines and phasing have not been announced; the project is clearly long-term.

Fig. 22. “Lines of Life” concept, Singapore. Source: Dezeen.

One of the most unexpected (yet unbuilt) examples is a proposal to connect Ronald Reagan Washington National Airport (DCA) with the adjacent Crystal City neighborhood via a linear park built over the existing highway — a comfortable public link between airport and city. The initiative came from the Crystal City Business Improvement District (BID), a non-profit established in 2006 and funded by local stakeholders.

Proximity to an international airport with 23+ million passengers/year and 9,000 employees — with growth potential — is attractive for district development. With growing interest in aerotropolis models, Crystal City aims to build an airport-oriented urban environment. A February 2018 feasibility study examined connection options; whereas the current trip from DCA to Crystal City can take 15+ minutes or $10+ by taxi, the proposed pedestrian link would cut the time by a factor of three.

The pre-design study considered several possible typologies for pedestrian routes, one of which was the High Line model. According to the authors of the study, this typology proved to be the most suitable, as it combines the pedestrian function with a comfortable public environment — and therefore became the foundation of the project concept. In addition, the proposal envisions the further development of existing green areas located between the airport and Crystal City.

Fig. 23. Airport–Crystal City connection concept. Source: Curbed.

Unlike the High Line, the D.C. concept includes a continuous canopy with variable section along the entire span, ensuring year-round comfort, and a more direct alignment to minimize travel time between airport and city. Estimated capital costs were $16–26 million, with $20,000–70,000/year in operating costs.

This may be the first case of a linear-park concept migrating directly into airport territory, typically reserved for utilitarian transport. It shows how urban-development trends now influence even such mono-functional infrastructure.

Fig. 24. View from the Crystal City side (concept). Source: UrbanTurf.

Why Linear Parks Keep Spreading

The number of linear parks worldwide continues to grow. First, they meet a strong public demand — especially in cities with rising population and density. Second, most cities retain industrial heritage — rail lines, factory lands, tunnels, roads, riverbeds, ports — needing re-imagining for contemporary needs. In the U.S., the Rails-to-Trails Conservancy (RTC) supports such conversions into public greenways and pedestrian routes. At the same time, participatory planning has become the norm: analyzing needs, context, and site potential helps to create “the right space in the right place at the right time.” Collaboration between active citizens and city authorities fosters a multifunctional environment for diverse user groups.

Fig. 25. Project for the connection between the airport and the Crystal City district. Source: Curbed.

A similar approach can be seen not only in linear parks but also in the revitalization of waterfronts, former port and coastal zones. These, too, are elongated structures whose renewal can spark wider urban transformation. Here the approach matters more than the form: the High Line “model” owes its success less to aesthetics (important as they are) than to a principled method of creating beloved urban spaces.

If the linear-park model works across countries, can it be applied in Moscow? With a careful urban analysis, community input, and the involvement of leading experts, such projects are bound to succeed. Thoughtful, comfortable public spaces are genuinely in demand in fast-growing metropolises and help people experience the city as a “place to live.”

Moscow is also developing ideas for continuous embankment redevelopment as a linear system. The Krymskaya Embankment makeover within Gorky Park showed how attractive and comfortable such spaces can be. In the near term, Shelepikhinskaya Embankment is slated for reconstruction as a green public space, and there is an idea to complete the Boulevard Ring as an unbroken pedestrian loop. These and other projects reflect the global trend of transforming linear structures into the arteries of the city.

The full text is published in TATLIN journal (in RUS).